I’ve been reading the excellent new run of Demo, comics by Brian Wood and Becky Cloonan.  If you are at all interested in comics, you should be reading these. They’re a series of standalone stories, so each week’s issue is self-contained. They have some supernatural element, but so far it’s been slight–the sort of supernatural element that you could chalk up to imbalanced perceptions on the part of the narrator.

If you are at all interested in comics, you should be reading these. They’re a series of standalone stories, so each week’s issue is self-contained. They have some supernatural element, but so far it’s been slight–the sort of supernatural element that you could chalk up to imbalanced perceptions on the part of the narrator.

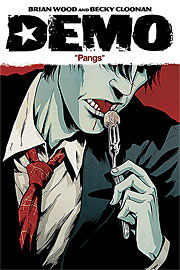

This week’s issue of Demo, called “Pangs,” was the best read of my week by far. It’s a story about a cannibal, and at some point I’m going to have to go through it panel by panel to figure out how the creators achieve the effect that they do. They don’t pull punches on the horror of cannibalism. It’s awful, and I spent the whole comic terrified of what the main character was about to do to himself or the people around him. On the other hand, they create so much sympathy for him that I wanted him to succeed, to be all right, to find a way to get away with it.

For one thing, this comic has excellent use of the second person. In the past, I’ve written on the confessional power of this tense:

“But as the reader gets more deeply into these stories, it becomes clear that the “you” isn’t really instructional. It’s more of the “you” that substitutes for an “I” in certain types of conversations. It’s used for statements like: “You know how sometimes you’re just angry at people who don’t deserve it.” But what I really mean is, “Sometimes, I’m mad at you when you don’t deserve it, and I’m sorry, but too afraid to say so.” It is a “you” that signifies a frightened “I,” and so contains a plea for identification, an upfront assumption that you and I participate in exactly the same sins.”

I stared in awe at the power of lines such as, “You realize it’s no good. You just can’t eat anything else…”

But before I go off completely on a rant about this particular issue, I also want to point to the other thing I find fascinating about Demo. Both Wood and Cloonan have included material in the back of each issue about how they stretch themselves for this series, playing with different concepts and different ways of telling stories. This material provides a shining example of the benefits of experimenting with style and genre.

Here’s something Cloonan wrote in the back of issue 1:

“Back when we started, I was actually surprised by how much Brian trusted me. I barely trusted myself–I had what I could only describe as stage fright, which I guess is a weird feeling to get while drawing, but as the issues went on (I’ll be the first to admit some more successfully than others), I came into a sort of sense of self about my art. For the first few issues I felt schizophrenic, but then I realized that all of this, all of DEMO was just aspects of me, and of Brian, and together the issues became more than just a sum of their parts.”

I think that’s beautiful, and I’ve experienced that feeling of stage fright when I have an idea that I like but am not sure I can pull off. Go read these.